Getting on the curve with rooftop solar

Following on from my last post, in this one I am focusing on our experiences of installing rooftop solar.

As new homeowners, the most obvious and available option for getting away from fossil fuels and reducing our energy costs was rooftop solar.

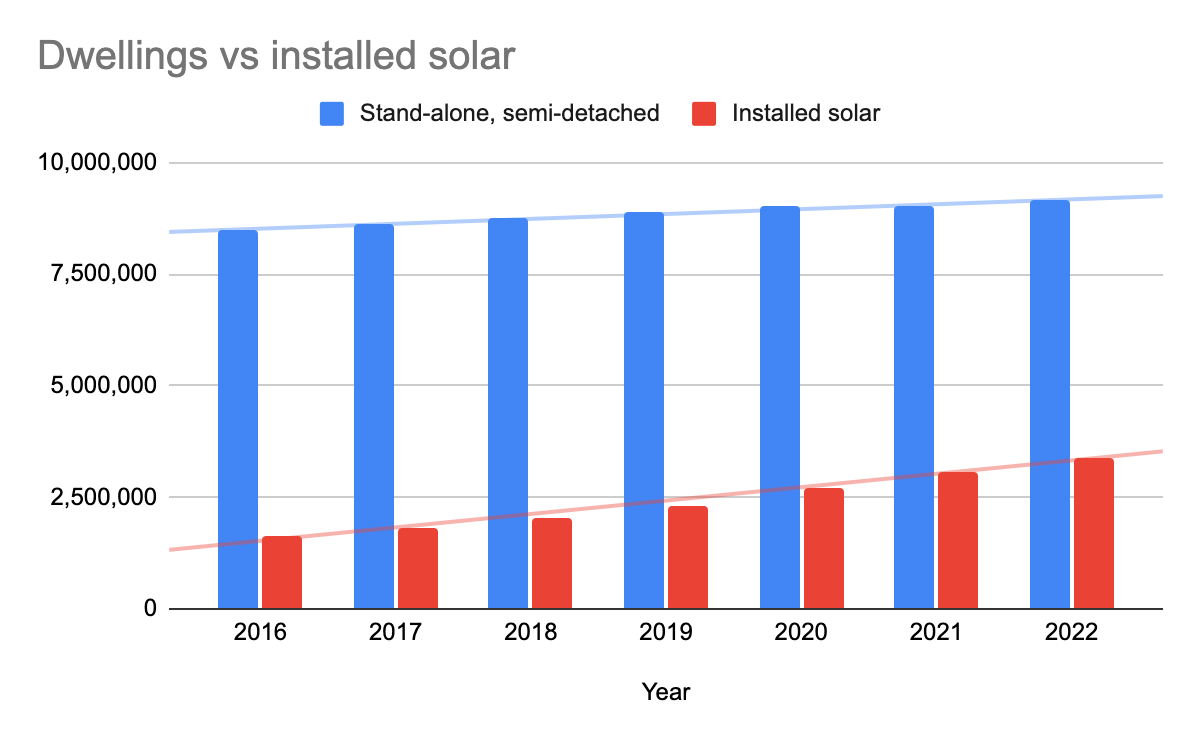

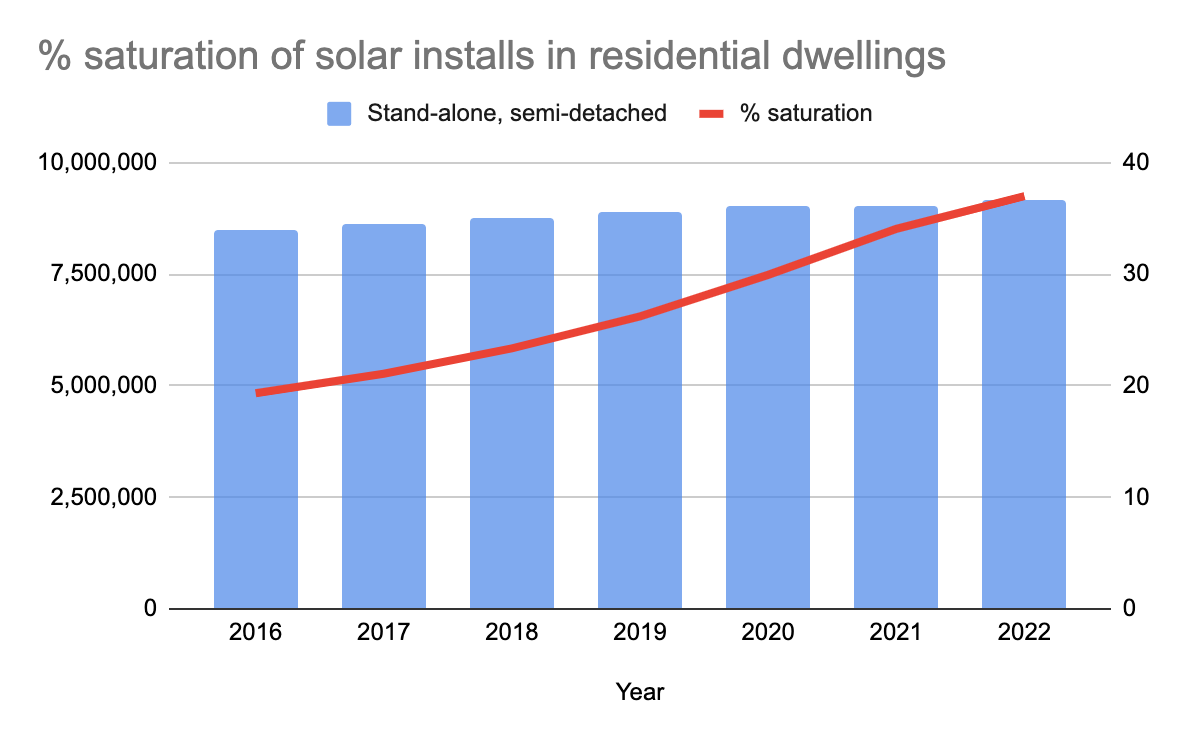

In 2017, about a quarter of Australian households had rooftop solar installed (a number that has only continued to accelerate in the interim), and although feed-in tariffs and government rebates helped improve the economics of the decision, this was something we were prepared to go ahead with, without the extra incentives.

For this investment we:

spent time researching installers to ensure we found one we were happy to hand our cash to.

read the advice on several renewable energy websites such as solar quotes (but also took this with a grain of salt).

made sure to educate ourselves about who the best manufacturers were of component parts (panels and inverters in particular)

made sure we were clear on our motives for the install ie: saving on power bills, not generating income from the FiT

Elapsed time from windfall (tax return in 2017) to install was more than nine months, and it cost a little beyond $10k to up and running (and ‘on the curve’).

Given the chance, I’d have pushed for us to embrace solar much sooner. Given the budget, I’d have pushed for a more expansive first step. But at least now we were in play.

Narrowing down the options

After shortlisting our preferred supplier, we still insisted on taking our time before locking in on a purchase (and as it happens, they did, too - insisting we spend time deliberating before deciding).

For us, priority was on these things:

Longevity of the hardware (cheaper systems tend to degrade quickly and so have a shortened operational lifespan)

Ethical supply chain (as best we could determine)

Warranty coverage and after sales support

Flexibility of the system (serial vs micro-inverters)

Ethics

As it stands (and as some squawky voices like to point out regularly), there’s a few unavoidable truths with solar:

most PV production comes from China, so the likelihood of forced labour being involved in the supply chain is high - especially for the cheaper brands, and

the ingredients for PV cells and their supporting hardware include some pretty toxic elements (regardless of the quality of manufacture). Going solar to be “green” is a misnomer, so being awake to this contradiction is important.

The waste chain for solar panels is largely undeveloped, with very little of the base materials reclaimed and recycled. In a lot of cases, decommissioned solar panels go to landfill.

Price

We didn’t prioritise price in our purchase decision. For us it was more important that whatever we bought would last a long time so we could avoid having to purchase again for as long as we could. This offsets some of the cons of taking on solar (see above), and provides a longer runway to pay down the investment.

Manufacturer

Decades of poor support from governments of all political persuasions has resulted in very little locally made or assembled options. In fact, Australia has just one local manufacturer remaining, and from a quality vs price standpoint they seem to sit around middle of the range.

We went with Canadian Solar panels, who are at the high end for price and quality; and so far at least, don’t have known issues in their supply chain. They also came with a 25 year functional warranty, which was more than most others provided.

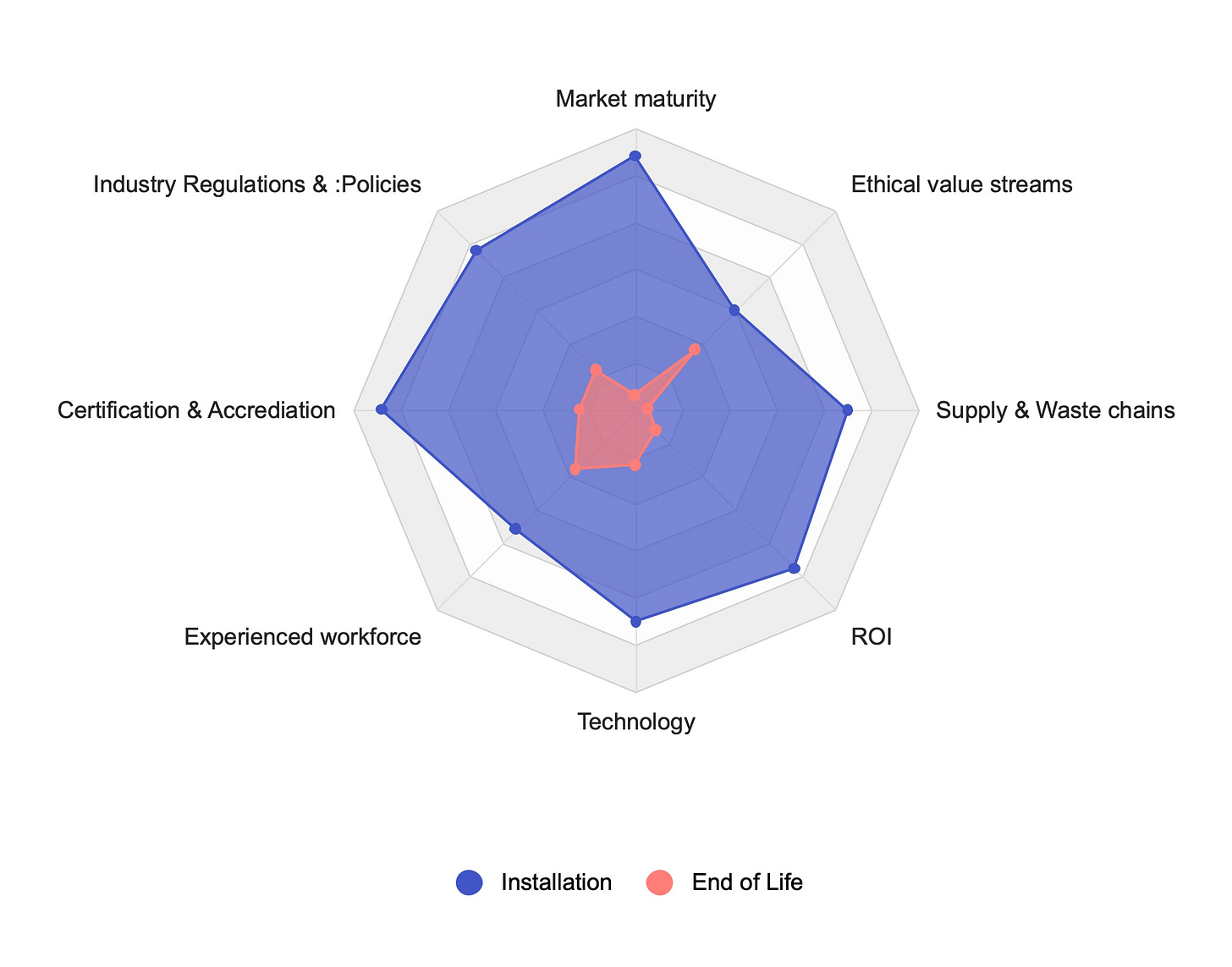

End of life

Whilst our solar supply chain has reached a state of maturity, we’ve got a long way to go when it comes to end of life and the waste value chain.

Maturity model

I’ve not been able to find any definitive criteria (especially with statistics to back them up) for how mature Australia’s solar supply and waste chains are. This in itself is telling. I’ve included some notation around how I’ve scored these criteria and acknowledge it is not robust. Hopefully the industry (or Governments) can begin to surface meaningful data to demonstrate all of this)

Market maturity

availability of choice around quality, price point and quality of manufacture1

Industry regulation and Policies

positive government interventions exist to drive innovation, investment, and uptake in the market.2

Certification and Accreditation

standardised training to ensure minimum standards in quality of site work.3

Experienced workforce

work is undertaken by professionals who are both adequately trained AND have sufficient on-site experience.4

Technology

Sufficiently evolved to provide asset owners with scalable and adaptable options that meet site requirements now and in the future.5

Generation asset output can be scaled up or down to meet home and grid demand.6

Asset owners can actively participate in the operation of their solar hardware.7

ROI

the investment pays for itself within a viable time frame ie: at LEAST within its operational life span.8

Supply and Waste Chains

The sourcing and supply of materials used in the manufacture of the product, and then the systems for decommissioning and disposal are well evolved and transparent.9

Ethical value streams

The supply chains for the product do not engage in exploitative labour practices or support/engage in other systems of oppression.

Environmental impacts from supply and disposal are actively managed to reduce harm.10

It’s another 20 years before the warranty expires on our panels. Our hope is they will continue to function reasonably well beyond this time, but either way, they will eventually stop producing electricity and will require replacement.

Whilst the technology for producing and installing solar panels has continued to develop over the decades, the full life cycle is patchy.

In our state of Victoria there’s a regulatory requirement for the waste chain from retired solar panels to be dealt with onshore, so when our panels do eventually need replacement, we have at least some confidence they won’t be shipped to a third world country to be disassembled or dumped in landfill.

Progress for disposing of non-functioning PV panels is still in its infancy but there have been some promising developments when it comes to recovery of previously impossible to extract silicon, which further reduces the negative footprint and develops value in the waste chain.

We need to ensure that the ingenuity that made this technology so ubiquitous continues to evolve, and the full waste cycle after the panels reach end of life will mature and scale to absorb the growing supply of retired panels as they are removed from roofs over coming decades.

Where (are we) on the curve?

At the time we got on board with rooftop solar in 2017, the Australian market was maturing to include the Early Majority. In the time since, that market saturation has accelerated to the point where soon, the late majority will join.

Our biggest hurdles were:

Getting to home ownership to be able to do what we wanted with the building

Finance for the purchase (banks such as Bank Australia now offer products specifically aimed at supporting this)

Access to the right level of information that would help us make a decision we were comfortable with (still sorely lacking).

If given a do over…

We would learn more about how the house is wired in:

Every home will have its own unique quirks - it’s vital people understand these before investing, so they can get the best returns.

Our house has more than a single power meter. There’s one for the general household, and another for a controlled load (which we believe is the central climate control).

The solar system is wired into just one of these, which may not be giving us the best outcome ie: the central climate control consumes the vast majority of our electricity, but as best we can tell, it’s not connected to the solar system and instead draws power from the grid even if the solar panels are pumping out 4-5kW).

We didn’t explore these questions rigorously when initially looking at what system to buy or how it should be connected. We relied too much on the consultants and sales people to be able to make the best recommendations for us.

Rooftop systems are complicated to expand (aside from buying and wiring in additional panels, it’s likely an inverter upgrade will be required), so until the tech evolves or our system reaches end of life, we’re stuck with the smaller system we have.

If we were making this decision again, I’d likely have pressed for at least a 7kW system, rather than the 5kW we installed (or at the very least, aimed for expandability).

The suppliers recommended this size based on our average household usage at the time, however this recommendation was based on historical usage, not future needs. Back then we didn’t have firm plans to purchase an EV, and although we have minimal gas appliances, our hot water and cooktop will eventually need to be changed over, which will place higher load demands on the house.

All these combined, will boost our electricity consumption and raise the likelihood our needs will become under served by the system we have.

We also weren’t thinking beyond the daylight hours and the role battery storage needs to play in home energy systems, nor the wider implications for the grid.

Get plugged in

Adding panels to your roof is among the easier steps for Australian homes to take to reduce their power bills, and their carbon footprint.

Yet despite this it may not be a straight line to success.

As someone who has navigated this course I’d say this: Lean into it, but be sure to educate yourself as you go, ask LOTS of questions, and be really clear about why you’re going ahead. If you’ve got clarity around your priorities now and in the future, this will help in deciding which system works for your needs.

It’s still not easy for home owners to make discerning choices when it comes to choosing solar. Purchase decisions are largely reliant on consultants embedded with the suppliers/installers.

Rebates on the cost of installation, with opportunities to earn from unused solar (there’s a whole debate about the suitability of FiTs - I’ll cover more when I discuss batteries)

The Clean Energy Council certifies all installers within Australia so we at least have a shared starting point for the skills of technicians.

As a nascent industry, access to technicians with lots of experience can be patchy. This will improve as the industry matures.

Modifying a system post install can be complicated and costly.

Household rooftop solar generally doesn’t include demand response capability, meaning most panels just keep pumping solar into the grid even when it’s not needed.

With the exception of some systems, the ability to directly manage where solar output is directed is limited. This becomes pertinent as high-load and/or storage systems are added to your home circuit.

Accurate data on how much you’re saving is hard to come by, because there are so many variables ie: pricing changes, change of supplier, consumption patterns etc. Best we have is aggregate data and averages but these don’t relate to a specific service address.

Supply chains are pretty stable now, but the waste chain is much like plastics - very little recovery of source materials, a lot goes to landfill.

For new installations, ethics are a challenge for home owners to reconcile. For decommissioned systems, the main issues are environmental damage, given the panels are largely stored to await a waste value chain developing.